Topic 4.1 - Individuals, firms, markets and market failure

Snapshot of the AQA syllabus topic area we’ll be covering in this post.

Economies and diseconomies of scale: PRODUCTION, COSTS AND REVENUE

AQA students must understand the following content [taken from the syllabus]

The difference between internal and external economies of scale.

Reasons for diseconomies of scale.

The relationship between returns to scale and economies or diseconomies of scale.

The relationship between economies of scale, diseconomies of scale and the shape of the long-run average cost curve.

The L-shaped long-run average cost curve.

The concept of the minimum efficient scale of production.

INFORMATION YOU NEED TO KNOW

Introduction:

When it comes to understanding the dynamics of production and cost efficiency, economies and diseconomies of scale are crucial. Economies of scale are the cost advantages that businesses experience as their production size grows, whereas diseconomies of scale are the potential cost drawbacks that may occur when production scales up. The concepts of internal and external economies of scale, the causes of diseconomies of scale, the relationship between returns to scale and economies/diseconomies of scale, how economies and diseconomies of scale affect the long-run average cost curve, the interesting L-shaped curve, and the idea of the minimum efficient scale of production will all be covered in this article.

Internal and External Economies of Scale: When a company increases output, internal economies of scale result from increased specialisation, improved efficiency in operation, and greater resource utilisation. A few examples are economies attained by more labour division, access to specialised technologies, price breaks for large purchases, and learning-by-doing effects. On the other hand, external economies of scale result from circumstances outside of a company and profit numerous businesses in the same sector or region. Improved infrastructure, a skilled labour pool, knowledge transfers, and the presence of industry clusters that encourage cooperation and knowledge sharing are a few examples of these.

Reasons for Diseconomies of Scale: Even though economies of scale have benefits, in some cases businesses may also experience diseconomies of scale. Diseconomies of scale can occur for a variety of reasons, such as difficulties with coordination and communication as organisations get bigger, inefficient bureaucracy, more complicated decision-making processes, and declining marginal productivity of inputs. Additionally, as businesses grow, they could experience difficulties managing a larger workforce, upholding quality control, and addressing problems with the effective use of resources.

Relationship between Returns to Scale and Economies/Diseconomies of Scale: Returns to scale describes the shift in output that happens when all of the inputs are changed proportionally. As production increases, economies of scale happen when returns to scale are larger than proportionate. This results in cost reductions. On the other hand, diseconomies of scale develop when returns to scale are less than proportional, leading to an increase in per-unit expenses. The industrial structure, technical developments, managerial skills, and market conditions are only a few of the variables that might affect economies of scale and diseconomies of scale.

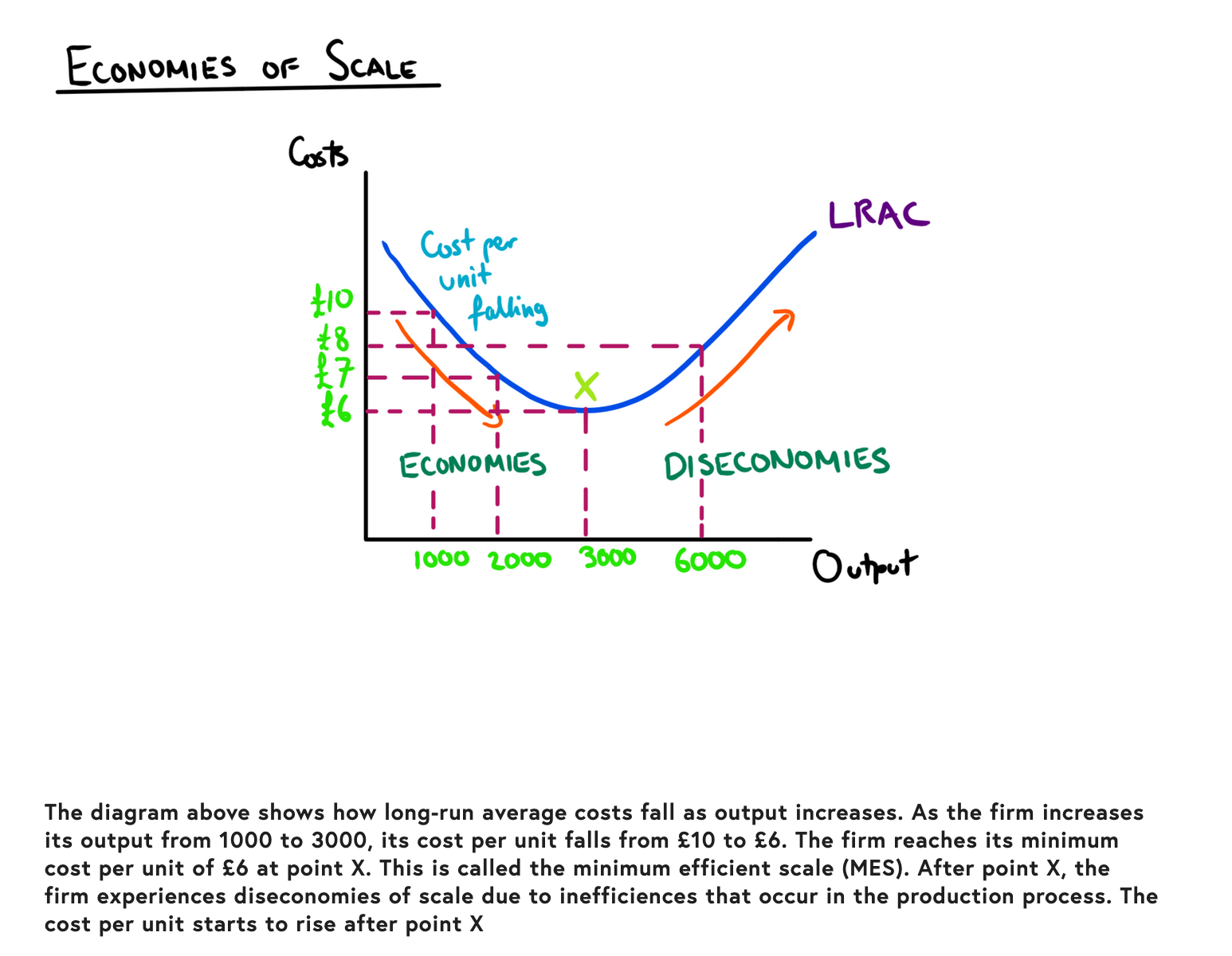

Relationship between Economies/Diseconomies of Scale and the Shape of the Long-Run Average Cost Curve: The long-run average cost (LRAC) curve is directly influenced by economies of scale and diseconomies of scale. Businesses frequently realise economies of scale during the early phases of industrial expansion, which results in a downward-sloping LRAC curve. The LRAC curve eventually hits a minimum point, which represents the smallest scale of production that is still efficient, after which diseconomies of scale take hold and the curve slopes higher.

The L-Shaped Long-Run Average Cost Curve: The L-shaped LRAC curve represents an exceptional situation in which businesses enjoy continuous returns to scale across a broad range of production levels. This implies that there are little to no economies of scale or diseconomies of scale, and the LRAC remains essentially flat. This tendency is seen in sectors with high fixed costs and little room for cost reduction through increased production. Businesses that operate at the bare minimum scale gain efficiency, but as output rises, they do not greatly profit from economies of scale.

The Concept of the Minimum Efficient Scale of Production: The smallest output at which a company may produce goods or services at the lowest possible average cost is known as the minimal efficient scale. This is where the LRAC curve's minimum value is found. Businesses can operate at or close to this magnitude and still attain maximum efficiency and market competitiveness. While surpassing it could result in diseconomies of scale and higher per-unit costs, falling below it might result in higher average costs.

For businesses looking to optimise their production processes, keep costs under control, and stay competitive, understanding the nuances of economies and diseconomies of scale is crucial. Firms can decide wisely about production expansion, resource allocation, and operational strategies, eventually encouraging long-term success in dynamic market environments, by understanding the elements that produce economies of scale and diseconomies of scale.

SPECIFIC KINDS OF ECONOMIES OF SCALE

Technical: the efficiency gains when a firm increases the scale of its operation yields lower costs per unit. For example, buying a bigger factory will cost you a little bit more but could give you a lot more volume to store your stock. Therefore, the cost per unit starts to fall. This is why big companies like Amazon opt for having huge central warehouses where all of the operations take place, rather than many small warehouses, each with high running costs. A lot of this is due to the law of large dimensions.

Specialisation and Division of Labour: a labour force that is specialised, divided and highly skilled will be more productive than a labour force that is the complete opposite. When your labour force can produce more for you in a given amount of time, then your cost per units fall. [Unless they start demanding higher wages! ;) ]

Purchasing: this refers to the cost per unit savings that you get when you buy more from your suppliers. Some may call it bulk buying. When a firm is bigger they can negotiate discounts when buying more and more goods and it brings down their average costs. Also, if a firm gets really big, they could become a monopsony. A monopsony is a firm with huge amounts of buying power in a market. In other words, they are a big buyer which sellers cannot afford to lose.

[Example: Tesco is a monopsony. Just a while back Unilever attempted to increase the price of its goods like Marmite by 10%. Tesco rejected this and because Tesco is such a big buyer (a monopsony) Unilever had to play the game by Tesco’s rules and not increase its price.

Marketing: this refers to the fall in costs per unit a big firm gains when doing big advertising campaigns. For example, a TV advert may cost thousands of pounds or even millions but if the result of the advert is millions of sales then the cost per unit is very low.

However, if your local hotdog stand did an advert on TV, it would still cost them millions but they’re not going to produce millions of hotdogs and therefore the cost per unit to them would be too high.

Financial: this is when big business are offered better interest rates than small businesses because they are borrowing more money and deemed a safer investment by banks. These savings bring down the cost per unit too.

For example, if I wanted to borrow £1 million, I might be offered an interest rate of 5%. In the first year that would be approximately £50,000 worth of interest. If Tesco wanted to borrow £1 million, they may be offered a rate of 1%, which would be approximately £10,000 of interest in the first year.

SUPPORTING DIAGRAMS

diagram to show traditional economies and diseconomies of scale

L-Shaped LRAC curve typically occurs in industries where there a is a higher proportion of capital fixed costs relative to human/labour costs. There is no or very little diseconomies of scale here. Certain businesses are able to scale up production without suffering too much from diseconomies of scale

![AQA ECONOMICS A-LEVEL SPECIFICATION SYLLABUS TOPIC 4.1 [ECONOMIES AND DISECONOMIES OF SCALE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55b690f2e4b076db679cd340/56a71d83-5cbd-4510-ac17-54910db3ba91/AQA+ECONOMICS+A-LEVEL+SPECIFICATION+SYLLABUS+TOPIC+4.1+%5BECONOMIES+AND+DISECONOMIES+OF+SCALE%5D)